If this were an orthodox evangelical Christian blog, the introductory question would just be a perfunctory way of this post saying, "Of course it is!" and giving some lame reasons why the Bible IS God's word. If you've read the previous two posts, then you probably know that I have some deep questions about the nature of the Bible and it's existence as a unit.

This question is not just rhetorical. This is a question that even the most fundamentalist Protestant Christian should take seriously, and understand their answer clearly. Romans and other ancient orthodox churches have their answer very clearly: The Bible is God's word, but so is the thrust of church tradition, of which the Bible is a part. Thus, the bastions of orthodoxy don't see the Bible as "God's word" in the sense of being unchanging, inerrant and foundational, like the most fundamentalist churches do.

The real reason that we need to bring up this question, is that the Bible doesn't make this claim for itself. Nowhere does the Bible claim for itself inerrancy or perfection. This is actually the claim of Islam for the Qur'an, when they say that the Qur'an came from heaven perfect and unchangable (although the historic records might ask them to reconsider that theology).

What does the Bible claim for itself?

An excellent example of this is I Timothy 3:16, "All Scripture is inspired by God and is profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction and for training in righteousness." Inspiration means led by God or by the Holy Spirit, but is far less than perfect or without fault. Rather, it speaks to a partnership between God and the author, but where the human element ends and the divine begins isn't determined. Also, since (we assume) Paul is writing I Timothy, our historians guess that the NT, for the most part, wasn't written. So Paul was pretty much speaking about what we call today the Old Testament. Yet Paul also says that "the law"-- another way of him talking about a portion of the Old Testament-- that "the law caused sin to increase," which is a strange thing to say about something that is perfect or infallible as some theologians claim of the Bible.

b. The OT and some New Testament passages are called "Scripture"

II Peter (included in the canon) claims Paul's writings as "scripture", and Paul speaks of a word of Jesus as "scripture". (II Peter 3:15-16; I Timothy 5:18) "Scripture" is a term that is used often in the NT to speak of a passage of the Hebrew Scriptures. What does this mean, really? The term "scripture" is just a form of the term "writing", although in context it implies some kind of authoritative writing. But this doesn't necessarily say divine writing, just authoritative for the community.

c. The Bible contains human history of what is God’s word

When we speak about "God's word", in the form of Scripture, we are really talking about God's speech. And the Bible contains much of this. The words of the prophets are full of "The Lord says", and we have recordings of God speaking to people, as well as giving law from Mt. Sinai. If we want to claim that the Bible is "God's word", this is the portion of the Bible that seems to most directly fit this claim, that which the Bible itself speaks of being God's speech. Prophetic speech is directly called "the word of YHWH" (II Sam. 22:31; Isaiah 1:10). The ten "commandments" are in scripture called the ten "words" which came directly from God (Exodus 34:28, where the word "commandments" is literally "words" in the Hebrew). But most of the Bible is not made up of speech of God, as opposed to the Qur'an.

(The following points will just be summaries, which will be expounded upon at a later time, hopefully)

d. Jesus is God's Word

One of the most remarkable statements in Scripture is that Jesus is God's word (John 1:1-14). This is fascinating because Jesus is a person, not a word or a speech. In what sense is he the "word of God"?

First, that Jesus is the mediation of creation. Just like God's spoken sentence "Let there be light" was a mediator to creation occurring, so does Jesus take the place of that creation. (John 1:3; Col 1:16)

Second, that Jesus only speaks what God the Father has given him to speak, making each word of his a word of God (John 7:16; 8:28)

Third, that Jesus only does what he sees the Father doing, so this makes his every action a word of God as well. God reveals all things to Jesus and thus Jesus is the perfect conduit for God's communication. (John 5:19-20)

Fourth, Jesus is granted knowledge of God that others do not have, and communicates that knowledge. (Matthew 11:27)

Of course, most of these claims are self-claims. If anyone came to us and said, "I am the word of God: everything I say and do is God" we might think about a loony-bin, but we wouldn't be ready to worship him. Unless of course, he came to us doing miracles never seen before and ended up getting resurrected from the dead by no one's hand but God's. The claim of Jesus is ludicrous, of course, unless one accepts the fact of the resurrection. If one accepts the resurrection, however, these claims are food for thought.

The rest of the points are made on the assumption that Jesus IS the word of God, which is the crux of the New Testament, and of the Christian interpretation of the Bible.

e. The OT is fulfilled in Jesus

According to the NT, the Hebrew Scriptures' primary purpose is to be fulfilled in Jesus.

The OT sets up a legal standard, which has never been obeyed, but in Jesus the Law is obeyed and surpassed (Matthew 5:17-22; John 5:46-47;

Every individual in the OT failed in some way, whether prophet, king, priest, judge or the nation Israel as a whole, but Jesus fulfills their potential (Matt 2:13-15; Acts 2:25-32; Hebrews 4:1-11);

Prophecy partially or left unfulfilled is fulfilled in Jesus (Luke 24:44, and many passages);

Jesus says clearly and acts clearly what was opaquely expressed in the OT (Hebrews 1:1-3; I John 1:1-3; John 1:16-18)

f. The NT is the witness of Jesus, especially the gospels

Paul is the earliest writer of the New Testament, and his work was to promote the lordship of Jesus, as he showed in his introduction to his seminal work, Romans (1:1-6). His writings were centered around the Lordship of Jesus, which he indicates in his favorite title for Jesus, Christ.

But in reality, although put down to paper later, Paul's writings are footnotes to the gospels, the oral versions of which were the heart of the first century church. These oral traditions and the four (or five) existent early gospels are the central scriptures of the Christian church. These are the texts that not only describe Jesus' teachings, but in detail lay how how Jesus' death and resurrection is the ultimate fulfillment of the Hebrew scriptures. Jesus as Messiah, or Christ, is the heart of the NT, and all other NT writings follow the gospels in that theme. To include the NT as the proper conclusion of the OT is to claim that Jesus is the conclusion of the matter of the Bible.

g. The Bible is not perfect, but Jesus’ interpretation of it is

As is noted by the NT authors, there are difficulties in concluding the Hebrew Scriptures with Jesus. Jesus welcomed all through faith, but the Hebrew Scriptures limited welcome to God to those who were male, Jewish and circumcised (the theme of Galatians and Romans). Jesus changed the center of the Law from a literal understanding of the ten commandments to a more flexible code of love and mercy (Matthew 12:1-13). A literal understanding of prophecy is to be changed to see Jesus as the fulfillment of all Hebrew prophecy. The NT writers liberally allowed for errors to be in the OT especially, not because the Bible isn't inspired, but because Jesus is the correct teacher and interpreter of the Bible. The Bible won't be properly understood without Jesus. (Matt 23:8; Luke 24:25-27; John 1:17; I Timothy 6:3-4; 2 John 1:9)

Even so, this biblical theology will follow the interpretation of Jesus. Jesus is the Teacher, we are the students. Of course, we will be following a particular interpretation of Jesus, that of the anawim (which will be explained soon). But Jesus is the core of understanding the Bible, whether Hebrew or Greek, whether Old Testament or New Testament.

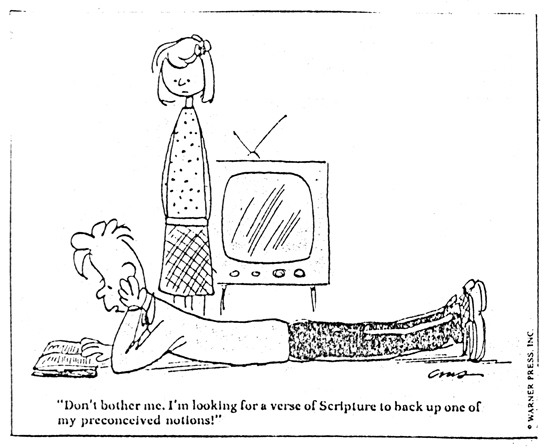

There shouldn't be any surprise here. Every person who approaches the Bible must have an interpretive key, for otherwise it is 66 books with very little to connect it. After all, how do we connect ancient Mediterranean love poetry, family history, religious history and apocalyptic? How do we see a unity between authors that are removed by possibly a thousand years or more? Many scholars have seen no unity but that which is imposed upon it. I think that if we look at the Bible as distinct books, with no connection, I think we are missing something that millions of readers have understood. I also think that if we impose our interpretation on the text, we do damage to the text.

Every religious group has imposed an interpretive key over the text of the Bible. Modern Jewish scholars do not read the original text without their rabbinic scholars and the hermeneutic principles they created in the first centuries BC and AD. The Eastern Orthodox churches use the first centuries of church fathers to understand the Bible. The Roman Catholic church uses their church tradition to understand the text. Many Protestants use a form of Luther's interpretation of Romans to understand the Bible. New interpretations of the Bible as a whole abound because the materials are so complex that they ask for multiple interpretations.

In this theology, I am less trying to discover the Bible (as much as I love it), as I am trying to discover Jesus. I want to see the Bible as he saw it, and explain reality in the way he explained it. And this is where we begin.

The Bible is NOT God's Word. Jesus is.

b. The OT and some New Testament passages are called "Scripture"

II Peter (included in the canon) claims Paul's writings as "scripture", and Paul speaks of a word of Jesus as "scripture". (II Peter 3:15-16; I Timothy 5:18) "Scripture" is a term that is used often in the NT to speak of a passage of the Hebrew Scriptures. What does this mean, really? The term "scripture" is just a form of the term "writing", although in context it implies some kind of authoritative writing. But this doesn't necessarily say divine writing, just authoritative for the community.

c. The Bible contains human history of what is God’s word

When we speak about "God's word", in the form of Scripture, we are really talking about God's speech. And the Bible contains much of this. The words of the prophets are full of "The Lord says", and we have recordings of God speaking to people, as well as giving law from Mt. Sinai. If we want to claim that the Bible is "God's word", this is the portion of the Bible that seems to most directly fit this claim, that which the Bible itself speaks of being God's speech. Prophetic speech is directly called "the word of YHWH" (II Sam. 22:31; Isaiah 1:10). The ten "commandments" are in scripture called the ten "words" which came directly from God (Exodus 34:28, where the word "commandments" is literally "words" in the Hebrew). But most of the Bible is not made up of speech of God, as opposed to the Qur'an.

(The following points will just be summaries, which will be expounded upon at a later time, hopefully)

d. Jesus is God's Word

One of the most remarkable statements in Scripture is that Jesus is God's word (John 1:1-14). This is fascinating because Jesus is a person, not a word or a speech. In what sense is he the "word of God"?

First, that Jesus is the mediation of creation. Just like God's spoken sentence "Let there be light" was a mediator to creation occurring, so does Jesus take the place of that creation. (John 1:3; Col 1:16)

Second, that Jesus only speaks what God the Father has given him to speak, making each word of his a word of God (John 7:16; 8:28)

Third, that Jesus only does what he sees the Father doing, so this makes his every action a word of God as well. God reveals all things to Jesus and thus Jesus is the perfect conduit for God's communication. (John 5:19-20)

Fourth, Jesus is granted knowledge of God that others do not have, and communicates that knowledge. (Matthew 11:27)

Of course, most of these claims are self-claims. If anyone came to us and said, "I am the word of God: everything I say and do is God" we might think about a loony-bin, but we wouldn't be ready to worship him. Unless of course, he came to us doing miracles never seen before and ended up getting resurrected from the dead by no one's hand but God's. The claim of Jesus is ludicrous, of course, unless one accepts the fact of the resurrection. If one accepts the resurrection, however, these claims are food for thought.

The rest of the points are made on the assumption that Jesus IS the word of God, which is the crux of the New Testament, and of the Christian interpretation of the Bible.

e. The OT is fulfilled in Jesus

According to the NT, the Hebrew Scriptures' primary purpose is to be fulfilled in Jesus.

The OT sets up a legal standard, which has never been obeyed, but in Jesus the Law is obeyed and surpassed (Matthew 5:17-22; John 5:46-47;

Every individual in the OT failed in some way, whether prophet, king, priest, judge or the nation Israel as a whole, but Jesus fulfills their potential (Matt 2:13-15; Acts 2:25-32; Hebrews 4:1-11);

Prophecy partially or left unfulfilled is fulfilled in Jesus (Luke 24:44, and many passages);

Jesus says clearly and acts clearly what was opaquely expressed in the OT (Hebrews 1:1-3; I John 1:1-3; John 1:16-18)

f. The NT is the witness of Jesus, especially the gospels

Paul is the earliest writer of the New Testament, and his work was to promote the lordship of Jesus, as he showed in his introduction to his seminal work, Romans (1:1-6). His writings were centered around the Lordship of Jesus, which he indicates in his favorite title for Jesus, Christ.

But in reality, although put down to paper later, Paul's writings are footnotes to the gospels, the oral versions of which were the heart of the first century church. These oral traditions and the four (or five) existent early gospels are the central scriptures of the Christian church. These are the texts that not only describe Jesus' teachings, but in detail lay how how Jesus' death and resurrection is the ultimate fulfillment of the Hebrew scriptures. Jesus as Messiah, or Christ, is the heart of the NT, and all other NT writings follow the gospels in that theme. To include the NT as the proper conclusion of the OT is to claim that Jesus is the conclusion of the matter of the Bible.

g. The Bible is not perfect, but Jesus’ interpretation of it is

As is noted by the NT authors, there are difficulties in concluding the Hebrew Scriptures with Jesus. Jesus welcomed all through faith, but the Hebrew Scriptures limited welcome to God to those who were male, Jewish and circumcised (the theme of Galatians and Romans). Jesus changed the center of the Law from a literal understanding of the ten commandments to a more flexible code of love and mercy (Matthew 12:1-13). A literal understanding of prophecy is to be changed to see Jesus as the fulfillment of all Hebrew prophecy. The NT writers liberally allowed for errors to be in the OT especially, not because the Bible isn't inspired, but because Jesus is the correct teacher and interpreter of the Bible. The Bible won't be properly understood without Jesus. (Matt 23:8; Luke 24:25-27; John 1:17; I Timothy 6:3-4; 2 John 1:9)

Even so, this biblical theology will follow the interpretation of Jesus. Jesus is the Teacher, we are the students. Of course, we will be following a particular interpretation of Jesus, that of the anawim (which will be explained soon). But Jesus is the core of understanding the Bible, whether Hebrew or Greek, whether Old Testament or New Testament.

There shouldn't be any surprise here. Every person who approaches the Bible must have an interpretive key, for otherwise it is 66 books with very little to connect it. After all, how do we connect ancient Mediterranean love poetry, family history, religious history and apocalyptic? How do we see a unity between authors that are removed by possibly a thousand years or more? Many scholars have seen no unity but that which is imposed upon it. I think that if we look at the Bible as distinct books, with no connection, I think we are missing something that millions of readers have understood. I also think that if we impose our interpretation on the text, we do damage to the text.

|

| It's okay, dear, no one does. |

In this theology, I am less trying to discover the Bible (as much as I love it), as I am trying to discover Jesus. I want to see the Bible as he saw it, and explain reality in the way he explained it. And this is where we begin.

The Bible is NOT God's Word. Jesus is.